Gaza

The Gaza Strip–poor, densely populated, largely cut-off from the world, and a focus of repeated violent conflict–remains a source of instability in Israeli-Palestinian relations. Over the past 25 years, basic human development and security indicators have gone from weak to fragile, and are significantly lower than for any other Palestinian community. Gaza’s population is among the most vulnerable and insecure anywhere in the world, and the area has one of the world’s highest population densities.

Controlled since 2007 by Hamas, a U.S.-designated terrorist group, Gaza presents a unique set of challenges to peacemaking and stabilization. Plans for Gaza’s rehabilitation depend heavily on cooperation between Israel, Egypt and the Palestinian Authority (PA) with support from the international community. Although increasingly cut-off, Palestinians consider Gaza to be an integral part of a future Palestinian state.

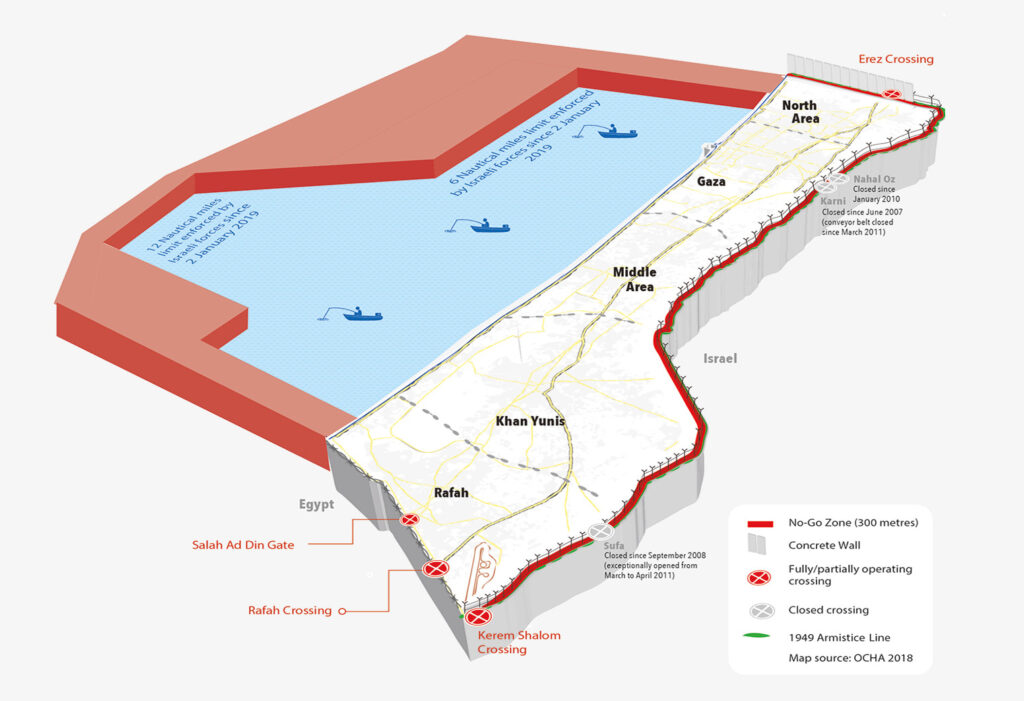

Map of Gaza and its borders (OCHA, 2018)

The October 7th attack and the war that has followed mark a watershed moment for the Gaza Strip. While some inside Gaza and around the world celebrated what they saw as a ‘prison break’, the atrocities which Hamas and those who broke through the barrier committed against the Israeli towns, villages and military posts near the enclave – over 1,200 killed, brutal sexual assaults and hundreds of kidnappings, including children – has led to an Israeli war that is far beyond what Hamas, Gazans and the entire region thought would occur.

Tens of thousands of Israeli soldiers, backed by an unprecedented airstrike campaign, have taken over Northern Gaza and have systematically made their way down south, clearing tunnels, and demolishing neighborhoods as they seek to destroy Hamas’ ability to govern the strip and threaten Israel. As of April 2024, the IDF was in control over almost the entirety of Northern Gaza, Gaza City, and large swaths of Southern Gaza including areas around Khan Younis.

In parallel, Israel has been conducting airstrikes on Deir al-Balah and Rafah. Much attention has been placed on a potential Israeli incursion into Rafah, the last major stronghold for Hamas. Though many Israelis argue that taking control of Rafah is a necessary step to rid the Gaza Strip of Hamas, many, including President Biden, also argue that it will result in massive civilian casualties as 1.5 million Palestinians currently reside in the city (up from 275,000 before October 7th). While the Biden administration supports Israel’s need to advance in Rafah, that support is conditioned on Israel putting in place a workable plan to relocate and better protect the impacted civilian population. Also, the Biden administration is arguing for a tactical military approach which primarily relies upon targeted operations against Hamas positions rather than a full ground invasion.

Given that Hamas is literally dug inside and underneath the civilian infrastructure of Gaza, the war has destroyed or damaged well over 50% of the buildings and much of the infrastructure. As of early February 2024, it is reported that more than 28,000 Palestinians have been killed and 1.8 million of the 2.1 million residents of Gaza have been displaced. Israel asserts that roughly 10,000 of the deaths are members of Hamas.

The humanitarian crisis in Gaza is undoubtedly dire and large percentages of Gazans are facing crisis levels of hunger. During the current war, as Israel increasingly comes under pressure to distribute adequate humanitarian assistance a variety of secondary options have developed. These include U.S. airdrops of Jordanian supplies and a land route transporting Moroccan supplies via Kerem Shalom. In March 2024, the U.S. and other countries built a pier off the coast of Gaza to increase the influx of humanitarian aid via Cyprus. It is also reported that Hamas continues to steal a significant amount of the humanitarian assistance.

After the war, Gaza will need to be completely rebuilt with the costs estimated at over $35 billion and rising. Beyond the immense infrastructure repairs that will be required in a post-war Gaza there are significant political and leadership challenges to address. The U.S., which has backed Israel through this war, has been pushing Israel to elaborate on its plans for a post-war Gaza. In February 2024, Israel released the first official plan for post-war Gaza stating that Israel would maintain security control and implement a civilian government composed of non-Hamas affiliated Palestinians.

There is speculation that the U.S. and several key Arab states are promoting an idea of a “grand bargain” in which Saudi Arabia would normalize relations with Israel in exchange for the creation of a path toward Palestinian statehood. However, Netanyahu has rejected any “unilateral recognition” of a Palestinian state.

PM Netanyahu has stated that Israel will not stop short of a “complete victory” in eradicating Hamas in the Gaza Strip. However, Hamas has been preparing for this war for decades and intends to withstand an Israeli assault. Therefore, experts are undecided on whether Israel’s strategic goal to rid the Gaza Strip of Hamas is feasible in any case and whether international pressure will halt Israel’s operations before their completion.

In any case, the inability of PM Netanyahu to provide a ‘day after’ vision that is satisfactory to Israel’s closest allies has hamstrung Israel in the eyes of the International community and threatens the possibility of the “grand bargain” with Saudi Arabia. The Biden administration, in concert with its regional allies, has pushed for a revitalized Palestinian Authority, backed by Arab allies, to play a prominent governing role in Gaza. So far, PM Netanyahu still rejects any PA involvement.

BACKGROUND

A major contributing factor to Gaza’s instability has been its long history of military rule. The area has been controlled by no less than four foreign military regimes since WWI (Ottomans, British, Egypt, and Israel), and was briefly under partial PA control (2005-2007), before the terrorist group Hamas took over in a violent coup.

From 1994-2005, the PA had limited autonomy in Gaza as a result of the Oslo peace process, though Israel maintained a heavy military presence in and around Gaza throughout this period.

During the first Arab-Israeli war (1948-49), Egyptian forces entered Gaza and continued to control the area for nearly 20 years. Gaza’s local population swelled with waves of Palestinian refugees from what became Israel. Egypt’s military rule ended after Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six Day War, widely known in Palestinian and Arab society as “Naksa,” meaning setback or defeat.

In December 1987, the first “Intifada”—a mass uprising of Palestinians against Israeli military rule—began in Gaza. Israel established a web of more than a dozen civilian settlements across Gaza beginning in the 1970s, ultimately withdrawing all of them in 2005.

Hamas1 An Arabic acronym for the “Islamic Resistance Movement” has long had its strongest base of support in Gaza, and its Islamist ideology2 Inspired by Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhoodand fierce opposition to peacemaking with Israel led to intense competition with the more secular Fatah party and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Hamas and Fatah also clashed throughout 2005 and 2006, following split results in Palestinian presidential and legislative elections. This competition turned into open warfare in 2007, during a brief coup in which Hamas seized power in the enclave. Hamas’ web of social services initially contributed to its high standing among some Palestinians, as did the perception that its leaders were not corrupt, helping Hamas win a surprise victory in PA legislative elections in 2006.

Long involved in terrorism, including responsibility for a number of attacks in which American citizens were killed or injured, Hamas was first designated as a terrorist group by the U.S. government in the mid-1990s. The group’s takeover of Gaza in 2007 and its militarization prompted Israel and Egypt to institute a near-total blockade. Low-level violent conflict between Israel and Palestinian armed groups in Gaza has been a near-constant feature, especially in the years immediately following Israel’s withdrawal in 2005. Tensions exploded in 2009, 2012 and again 2014, when Hamas and Israel fought three wars, the last stretching on for over 50 days and leading to widespread destruction and human suffering. In 2021, following rising tensions throughout Ramadan in Jerusalem, Hamas launched rockets at Jerusalem which started 11 days of fighting with over 4,000 rockets fired at Israel and heavy Israeli airstrikes in return. By the time a ceasefire was reached, 248 Palestinian and 12 Israelis were killed with hundreds more injured.

The intense rivalry between Hamas in Gaza and the PLO and PA leadership based in Ramallah in the West Bank has left the Palestinian national movement effectively divided geographically and ideologically—and it has further complicated the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

GAZA’S HUMAN CRISIS

The extent of Gaza’s human development challenges cannot be understated. A large majority of the area’s two million residents live in poverty and are on food support, largely provided by the United Nations, which maintains a vast social services footprint in Gaza. Energy shortages are common, unemployment is widespread, and severe water and sewage problems cause a wide range of related problems, many of which directly impact Israel. The area’s modest natural water supply has been depleted and permanently damaged through seawater intrusion. The area’s lack of sewage treatment capacity has led to massive public health and disease outbreaks, as well as causing costly environmental crises that have polluted Israeli beaches and closed Israeli desalination plants. A 2018 study by the Rand Corporation, a leading non-partisan U.S. think tank, found that “more than a quarter of all reported disease in Gaza is caused by poor water quality and access.”3 See Rand Corporation, Shira Efron et. al. 2018, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2515.html Gaza’s population is vulnerable to violence, and is afforded few opportunities to leave the overcrowded area.

In a series of widely read reports over the past decade, the United Nations has declared Gaza “unlivable,” and raised alarms about the area’s systematic “de-development.”4 See United Nations, https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/07/561302-living-conditions-gaza-more-and-

more-wretched-over-past-decade-un-findsIn addition to the U.N., a variety of international actors play significant roles, including Egypt (security and diplomatic mediation with Israel), and the European Union, Turkey and Qatar (humanitarian assistance).

The humanitarian crisis in Gaza has only worsened in the aftermath of October 7th. According to a March 2024 report, famine is likely to occur in Northern Gaza by May and may spread to the rest of the Gaza Strip.

LEGACY OF 2005 DISENGAGEMENT

The legacy of the unilateral Israeli “disengagement” from Gaza looms over any discussion of security in a two-state solution. In 2005, the Israeli government evacuated all 8,000 Israeli settlers from Gaza and handed over responsibility to the PA. But in light of the subsequent Hamas coup and the repeated rounds of violence, the Gaza withdrawal has eroded Israeli trust in the notion of “land for peace,” and some fear that a larger withdrawal from the West Bank could lead to another “terror state” on Israel’s borders. More recently, as a result of the events of October 7th, there have been increasing calls from Israelis to resettle areas evacuated in 2005.

SOLUTIONS

Despite Gaza’s many challenges – the Hamas-Israel conflict, Hamas-PLO rivalry, huge social and health challenges, a devastated economy – there are a number of well- developed solutions that could be adopted.

In terms of addressing the energy-water nexus, tapping Gaza’s off-short gas reserves would be a boon. Proposals for building an off-shore docking facility, and/or a dedicated and monitored port in nearby Cyprus could solve one of the region’s toughest challenges: access and movement of goods. Finding workable solutions that would reduce the heavy restrictions on Gaza’s fishing industry, a mainstay of the local economy, would also have a major positive impact.

A 2014 United Nations Security Council proposal—supported by Israel—included a framework for reconstruction, increased movement and access, and demilitarization. It would have addressed a wide array of Gaza’s most immediate challenges, though the effort fell victim to the internal Palestinian power struggle. Nonetheless, it demonstrated that there is international support, including from Israel, for considering pragmatic solutions and for increasing outside support.

Greater Israeli trade with Gaza, and more labor permits – which 20 years ago were at a far higher level – would provide another source of sustainable economic recovery.

A recent study from the Brookings Institution called for a new U.S. approach, one less tied to a negotiated permanent status agreement with Israel and aimed more at stabilizing Gaza and addressing the area’s “dire humanitarian and economic conditions” and redirecting diplomacy toward preventing “future conflicts between Hamas and Israel.” Furthermore, it calls for pursuing the political and physical reintegration of Gaza with the West Bank, which would also address the area’s underlying isolation.5 See Hady Amr et. al. “Ending Gaza’s Perpetual Crisis,” Brookings Institution, December 2018,

https://www.brookings.edu/research/ending-gazas-perpetual-crisis-a-new-u-s-approach/